| Written by: | Stephanie Milsom |

| Date posted: | December 14, 2018 |

| Posted in: | Home / Information / |

‘Tis the season to be jolly!

Christmas is celebrated across the Christian world and – in more recent times – in other non-Christian countries. Its increasing popularity is perhaps due in part to the appeal of Christmas decorations, Yuletide gift-giving, and festive feasts. But how much do you actually know about this famous time of year?

The origins of Christmas

Pagan roots

For many of us, the festive season we celebrate today is secular, though some of our modern traditions have their roots in pre-Christian paganism and early northern European religions. Most specifically, Christmas has ties to Yule, a midwinter festival celebrated by Iron Age Germanic peoples.

Father Christmas, or Santa Claus, or Saint Nicholas, or Sinterklaas, or Grandfather Frost – whatever your name for him – is believed to be derived at least in part from Odin, the All-Father of Old Norse mythology. Taking the form of an old and bearded man, Odin had many names and could take many forms. One of his names, jólfaðr, literally translates as ‘Yule Father’. Norse jól was used to refer to both the Gods in general and to feasts, a common feature of Nordic mythology. The ‘Feast Father’, or ‘Gods’ Father’, was known for welcoming soldiers to his gigantic hall in Valhalla, where the honoured men would feast and drink until the end of days. The 12 days of Christmas, the Yule log, Christmas wreaths, and the Christmas tree all date back to at least 900 AD, when the Yule festival was celebrated across 12 winter days.

Winter feasts and ceremonies were common during pagan times due to people’s close relationship with the seasons and their belief in fickle gods – another year survived, then, was something to be celebrated. Today’s Christmas lights have their roots in the use of fire and candles to drive out the darkness and ward off evil spirits walking the Earth during the Long Night, or the winter solstice. These customs are incredibly long-standing – in fact, scholars believe that humans have observed the solstice since Neolithic times!

Christian influence

It is well-known that Christianity co-opted important dates from the pagan calendar in order to ease its spread throughout the general populous. Thus, despite the fact that Jesus’ exact date of birth is not mentioned anywhere Scripture, we celebrate it on December 25th. This date was commemorated as the winter solstice in the Roman calendar – long-connected with birth and rebirth, the solstice was an obvious choice for the date of the most important Christian celebration.

The first recorded Christmas – as a celebration of Jesus – was held in Rome in 336 AD. By the 5th century AD, when the tradition of Midnight Masses was first recorded, Europeans associated the Yuletide with the Son of God and any festivities were largely centred on religious observance. By the Middle Ages, Europeans revered Saint Nicholas, a Greek bishop famed for his generosity to the poor. Gifts were exchanged in his honour on December 6th, Nicholas’ name day, though some in the Church did not agree with this tradition. Martin Luther was the first to argue to that gifts should be given on Jesus’ birthday as a way to honour Christ, rather than on any other saint’s day. He was also the first to suggest Christkindl, a small sprite-like female figure evocative of the Baby Jesus, as the Christmas gift-bringer.

Merry-making in the Middle Ages

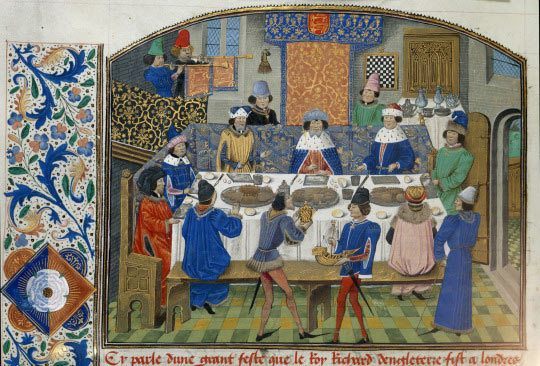

The tradition of merrymaking during winter first appeared in England during the High Middle Ages (1100 – 1300), which had its basis in the earlier pagan practices. By this time, the term ‘Christmas’ had replaced ‘Yuletide’ and was in wide usage across the country. Elaborate revelry and pageantry were popular in this period, with grand houses and wealthy businessmen holding Feasts of Fools over Christmas, including characters such as ‘Captain’ or ‘Lord’ Christmas. King Richard II of England is said to have hosted a Christmas party in 1377 at which 28 oxen and 300 sheep were eaten!

By the 16th century, the period was personified by the jolly Father Christmas, a benevolent figure closely linked to European figures such as Sinterklaas (a derivative of ‘Saint Nicholas’) and Christkindl (literally ‘Christ Child’). Originally cloaked in green – perhaps due to contemporary obsessions with evergreen plants surviving the winter – Father Christmas typified the spirit of good cheer, bringing peace, joy, and good food to all at Yuletide.

Traditional festive dishes such as plum porridge or pottage – the spiced, meat-filled ancestor of Christmas pudding – and roasted fowl with potatoes date from this period. Sweet spices such as cinnamon and cloves brought back from the Holy Land during the Crusades appeared in English cuisine as early as the 1300s and were popularised during the 15th and 16th centuries. The use of brandy in early Christmas pudding mixes – which sweetened the batter after fermentation during the advised ‘resting period’ – helped to turn the once-savoury dish into a dessert. Though normal families might have eaten duck or goose at Christmas, rich lords dined on roasted ham, peacock, or swan. Henry VIII is said to have been the first person to dine on Christmas turkey, popularising the dish and cementing its place in English festive tradition.

During Protestant rule in England, Christmas was actually banned for around 15 years! Its association with Catholic ‘popery’ and gluttony made it a target for puritanical rulers, and the festival wasn’t allowed to be celebrated again until after the 1660 Restoration. This had dire consequences for Father Christmas and all related celebrations; Christmas customs largely died out in England during this period and weren’t revived again until the Victorian era.

Victorian revival and beyond

The common fascination with old-fashioned and ‘homely’ traditions such as Yule logs and Christmas puddings contributed to the subsequent popularity of Father Christmas, seasonal merriment, and Yuletide gift-giving. Charles Dickens popularised the familiar image of the genial spirit of Christmas in his 1843 novel A Christmas Carol, wherein a green-cloaked Ghost of Christmas Past sprinkles the Essence of Christmas as he guides Scrooge through London. This happy figure harked back to a mostly fictitious idea of ‘Merrie England’, when people were just and loyal and everyone was kind to one another. This was an idea that blended well with the joyous and jolly connotations of Father Christmas.

The reindeer that pull Santa’s sleigh are a relatively late invention, having first appeared in an anonymous poem in American press in the 1800s. Red-nosed Rudolph actually comes from a 1939 advertising campaign for an American department store. Elves, meanwhile, were first referred to in publication in the 1870s in an American women’s magazine. Companions are common for mainland European gift-givers, sometimes as helpers (in the case of elves) but more usually as antagonists, such as Black Pete, Krampus, and Knecht Ruprecht, all of whom carry reeds or birches with which to punish naughty children.

The jolly figure as we know him today is largely of American origin. Mixing cultures in the New World combined Dutch, English, and Germanic customs to make ‘Santa Claus’ (a phonetic derivation of Sinterklaas), who first appeared in the American press in 1773. Though originally different figures, today Father Christmas and Santa Claus are synonymous with one another in the western world, and many of their associated traditions are celebrated throughout the world. Santa’s red cloak was cemented into common knowledge following Coca-Cola’s 1931 advertising campaign, featuring the smiling cotton-haired figure we know and love today.

Christmas around the world

- Christianity’s influence on the holiday has made Nativity scenes popular in many traditionally Catholic countries. Some depictions include local folk figures or modern symbols of the community, such as cacti and flamingos in Mexican nacimientos,or politicians in Italian nativity cribs from Naples!

- Across the world, it’s actually more common to celebrate the holiday and exchange presents on December 24th rather than the 25th. This custom is based around Midnight Mass, attended on Christmas Eve, with the Christmas meal eaten either before or after this service. In Poland, for example, many houses serve 12 dishes to symbolise the Bible’s 12 Apostles. The fare is very fish-based, with little or no red meat – this is said to be in remembrance of the animals who accompanied Jesus in the stable in Bethlehem. The main dish is fried carp with potato salad, and beetroot soup. The meal begins with the breaking of the opłatek, a printed wafer blessed by the church, which symbolises the body of Christ and the dinners’ unity with him.

- In hotter countries, where a ‘White Christmas’ is almost never experienced, seasonal customs are very different to those we celebrate here in the UK. In Chile, for example, fireworks and paper lanterns are lit at the stroke of midnight and partying goes on long into the night. After sleeping, perhaps past noon, families and friends often head to the beach for a barbecued lunch and an afternoon under the sun.

- Japan has, perhaps unsurprisingly, one of the more queer Christmas traditions. Not traditionally a Christian country, Yuletide customs are relatively recent, and most have entered the country from the USA via television. Dating back to a hugely successful advertising campaign in 1974, many locals now eat KFC as their Christmas dinner! The fast food chain is now so popular that some people place their orders months in advance. As in many countries, Christmas Eve is celebrated more than Christmas Day – the 24th is seen as a romantic day very similar to Valentine’s Day, and young couples will often spend the day together rather than with their families. Another quirk of Japanese Christmas: what locals call ‘Christmas cake’ is actually a light sponge topped with strawberries and whipped cream – not a sultana in sight!

- In Medellín, the festivities kick off with the ‘Day of the Little Candles’ on December 7th. In honour of the Immaculate Conception, the entire city is decorated with lanterns and candles on almost every available surface. What follows is a city-wide extravaganza starting on La Playa Avenue, crossing and decorating the River, and down to the Guayaquil Bridge. The Christmas meal is eaten after families return from Midnight Mass, and presents are opened only after midnight. The resulting party may go on well into the early hours of the morning on Christmas Day, which is mainly a time for rest and recovery from the festivities.

- Though many festive traditions seem to be shared across the world – with a few tweaks here and there – there are several that don’t seem to make sense at all to the outside viewer. Take La Befana, for example, the good Italian ‘witch’ who is married to Santa and flies around on a broom delivering sweets to children on the eve of Epiphany. Like Western Santa Claus, she enters the house via the chimney in order to bestow her gifts. Also like Santa Claus, she might bring naughty children lumps of coal – nowadays rock candy coloured black.

- In Dutch tradition, Sinterklaas – an idealised version of Saint Nicholas – lives in Madrid and arrives in Holland in November with his companion, Black Pete, by steamboat! Sinterklaas then tours the cities on horseback and greets children, whilst his helpers toss sweets and biscuits into the crowds. He leaves presents in children’s shoes on the night of December 5th. Though some Dutch families will also celebrate Christmas Day, Saint Nicholas’ Day is more popular, and Sinterklaas is widely considered the older cousin of Santa Claus.

- Across the world, winter gift-givers are often accompanied by a less-than-friendly figure, such as Austria‘s Krampus. Harking back to a medieval fascination with masked devils and demons, Krampus is a fearsome creature who accompanies Saint Nicholas and threatens badly-behaved children. A horned beast with cloven hooves and a long, lolling tongue, he is visually very similar to common depictions of the devil and carries a bundle of birch branches or a whip with which to swat children.

- In many Spanish-language countries, the Day of the Innocents is celebrated on December 28th. This is a strange festival meant to remember the children killed by King Herod – you’d be forgiven for thinking the event would be a sombre affair. In fact, it’s similar to April Fools’ Day; families and friends play practical jokes on one another, and any news should be taken with a pinch of salt on this day; media outlets love to get involved! This custom may have come from the likeness between the Spanish los inocentes, meaning ‘the innocent ones’, and inocentadas, meaning ‘pranks’. Some, however, argue that the tradition of joke-playing symbolises the great joke that, while King Herod thought he had succeeded in eliminating the threat against him, Jesus was in fact safe and well and preparing to change the world.

- The last day of the Christmas season for most of the world is Epiphany, which falls on January 6th. This date marks the end of the 12 Days of Christmas and commemorates the Magi’s visit to Jesus in Bethlehem. Unlike in the UK, where the meaning of this date has largely been lost, many European and South American countries still honour this date. Sweet round buns, often decorated with bright sugary sweets to symbolise regal jewels – such as the Portuguese Bolo del Rei, or King’s Cake – are eaten, and many cities will hold a King’s Parade, complete with floats and giant figurines.

Christmas 2018

However you celebrate, wherever you are, we at Apple Language Courses wish you a …

عيد ميلاد مجيد (Eid Milad Majid!)

Blog Categories

- Activities (4)

- Yoga (1)

- Christmas Courses (17)

- Food (21)

- Recipes (4)

- Information (83)

- Instagram (11)

- Language fun (11)

- My travel journal (15)

- Sample Programmes (2)

- Video Guides (11)

- Locations (430)

- America (4)

- Argentina (15)

- Bariloche (4)

- Buenos Aires (8)

- Cordoba (2)

- Mendoza (1)

- Australia (1)

- Sydney (1)

- Austria (4)

- Brazil (5)

- Maceio (2)

- Salvador da Bahia (2)

- Sao Paulo (1)

- Canada (8)

- Chile (4)

- China (7)

- Colombia (2)

- Costa Rica (8)

- Flamingo Beach (5)

- Monteverde (1)

- Cuba (8)

- Havana (3)

- Santiago de Cuba (3)

- Trinidad (2)

- Czech Republic (2)

- Prague (2)

- Dominican Republic (1)

- Santo Domingo (1)

- Ecuador (3)

- Egypt (2)

- Cairo (2)

- England (23)

- Bournemouth (1)

- Brighton (1)

- Bristol (1)

- Cambridge (2)

- Liverpool (9)

- London (3)

- Manchester (2)

- Oxford (1)

- Portsmouth (1)

- France (53)

- Germany (49)

- Greece (4)

- Guadeloupe (3)

- Guatemala (2)

- Antigua (2)

- Ireland (4)

- Italy (78)

- Japan (3)

- Latvia (1)

- Riga (1)

- Malta (3)

- Mexico (10)

- Cuernavaca (1)

- Guadalajara (1)

- Guanajuato (1)

- Mexico City (1)

- Playa del Carmen (6)

- Morocco (1)

- Rabat (1)

- Netherlands (4)

- Panama (1)

- Bocas del Toro (1)

- Boquete (1)

- Peru (5)

- Poland (2)

- Portugal (9)

- Russia (6)

- Moscow (2)

- St Petersburg (2)

- Scotland (2)

- Edinburgh (2)

- Spain (89)

- Alicante (1)

- Barcelona (13)

- Bilbao (1)

- Cadiz (1)

- Costa Adeje (1)

- El Puerto (3)

- Granada (5)

- Ibiza (1)

- Lanzarote (1)

- Madrid (6)

- Malaga (15)

- Marbella (1)

- Murcia (1)

- Nerja (4)

- Pamplona (1)

- Puerto de la Cruz (3)

- Salamanca (3)

- San Sebastian (7)

- Santiago de Compostela (2)

- Seville (5)

- Tenerife (6)

- Valencia (9)

- Vejer de la Frontera (2)

- Sweden (2)

- Stockholm (1)

- Switzerland (2)

- Montreux (1)

- Ukraine (2)

- Kiev (2)

- United Arab Emirates (1)

- Dubai (1)

- Uruguay (1)

- Montevideo (1)

- New Schools (14)

Company Number: 08311373

Company Number: 08311373